by Lisa Mcintosh

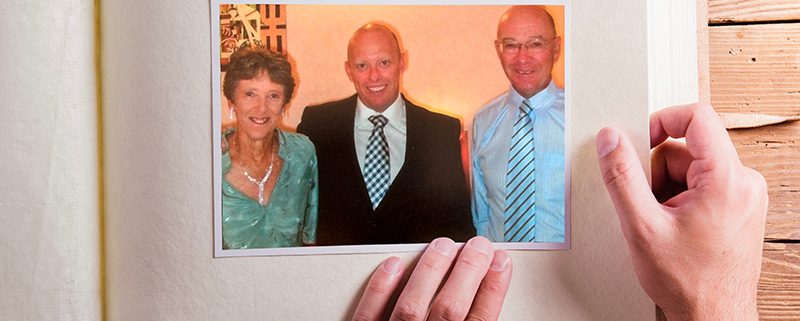

In 2008, 39-year-old Darren Forrest contracted a virus that caused his kidneys to malfunction. Unless a compatible kidney donor was found, Darren would need to go onto the life-altering routine of dialysis, something medical professionals wanted to avoid. Family members were tested for compatibility and, while his mum, Marg, was very keen to be the donor, only his father, Geoff, was a match.

Willing to donate a kidney to his son, but also feeling as though he had no choice in the matter, Geoff, who was then 65, underwent a year of very extensive medical tests – between 20 and 30 in number according to his estimates.

However, in the last scan, doctors found lumps on his lungs. The transplant was put on hold due to concern that Geoff might have cancer. The medical team decided they could test again three months later to confirm that the lumps were benign.

‘The whole process took more than a year from start to finish’, says Geoff, who taught and then tutored at Immanuel College in suburban Adelaide across

a period of more than 35 years from 1981. ‘And they tested for everything. It was very reassuring to me. Because I was older, they had to check absolutely everything to ensure that I wasn’t going to get cancer or anything that would leave my remaining kidney damaged.’

While the lead-up to the transplant impressed Geoff, what happened afterwards was painful – physically and emotionally. Darren was in intensive care after the operation with nursing support throughout, but Geoff was put in a public ward that accommodated a violent patient with dementia and then was sent home from hospital after two days despite not feeling well enough to be discharged. He split his stitches due to the extreme pain and the effect of the drugs he was given, but was unable to access promised nursing support through a 24-hour hotline.

Naturally, though, there were plenty of good outcomes of Geoff’s sacrifice. The amount of the chemical waste product creatinine – which is removed by the kidneys – in Darren’s system had been at near-fatal levels before the transplant, but the improvement was dramatic. ‘The transplant happened at about 8am and by midday, it had gone down from 2000 to 200’, Geoff says. ‘So, the kidney started working straight away – it was incredible.

‘The transplant also enabled Darren to have a child so, indirectly, I was responsible for that, too. So, all that was really good, but it was much harder on me than I thought it would be. I still would have done it, don’t get me wrong. But I also resented the fact that I felt that I didn’t have a choice.’

Thankfully, Geoff’s experience of a lack of post-operative medical support was not typical of other donors that year from the same hospital. The donors were asked to share their experiences with health practitioners at a meeting. ‘All these other people were saying it was the best experience of their life’, Geoff says. When it came to his turn, he says the surgeon was ‘shattered’ by what had happened to him, because she said they hadn’t paid enough attention to the donors while focusing their attention on the recipients.

Geoff, who was raised in the Methodist church and had taught at an Anglican school in New South Wales, before joining the staff at Immanuel College and becoming involved with the Lutheran church through the chapel services there, says he has often pondered the interplay between Christian living and the ethics of organ donation. ‘Is it playing God or is it just like any other advances in medical treatment?’, he asks.

However, it was his second experience with organ donation and, more particularly, the sudden death of his wife of more than 49 years, Marg, that he says shook his faith to the core.

In 2015, Marg, who had also been a teacher and, like Geoff, was at that time tutoring Indigenous students who boarded at Immanuel, fell one day at work and hit her head. Otherwise fit and healthy, Marg played golf and worked in the two days following before a severe headache led to her being hospitalised. Within a further 24 hours, she was in a coma from which she never recovered. Marg was on life-support for two days, with Geoff and his children, Darren and Kerry, keeping a hospital bedside vigil.

Geoff knew Marg wanted to be an organ donor. However, when the family was told that donating her heart and lungs would mean a further two days on life support, it was too much to ask. ‘And so we said. “No, we don’t want that”’, Geoff says. ‘We were able to donate two kidneys, and that’s what she would have wanted because of Darren.’

Even more traumatic for the Forrests were the three hours of interviews that followed Marg’s death with the workplace health and safety regulator and the organ donation representatives, including highly personal and even ‘revolting’ questions. ‘It was hell’, says Geoff, who hopes there will be procedural change that will save other families going through what they endured.

‘The whole thing with Marg’s death rocked my faith because I’m thinking, “Why me?” I’ve had a friend who was five minutes from dying due to blocked arteries – now they’ve had a quadruple bypass and they’re fit as a fiddle. And I’m thinking, “Why wasn’t Marg given that chance?” I don’t like the suggestion that God simply needs her more than others.’

However, Geoff says the tragedy has changed his outlook on life and relating to loved ones. ‘I’ve learnt that life is very precious’, he says, adding that it’s critical to treasure the people you love while you have them. ‘And remember to tell them that you love them.’